Learn not Blame - discuss

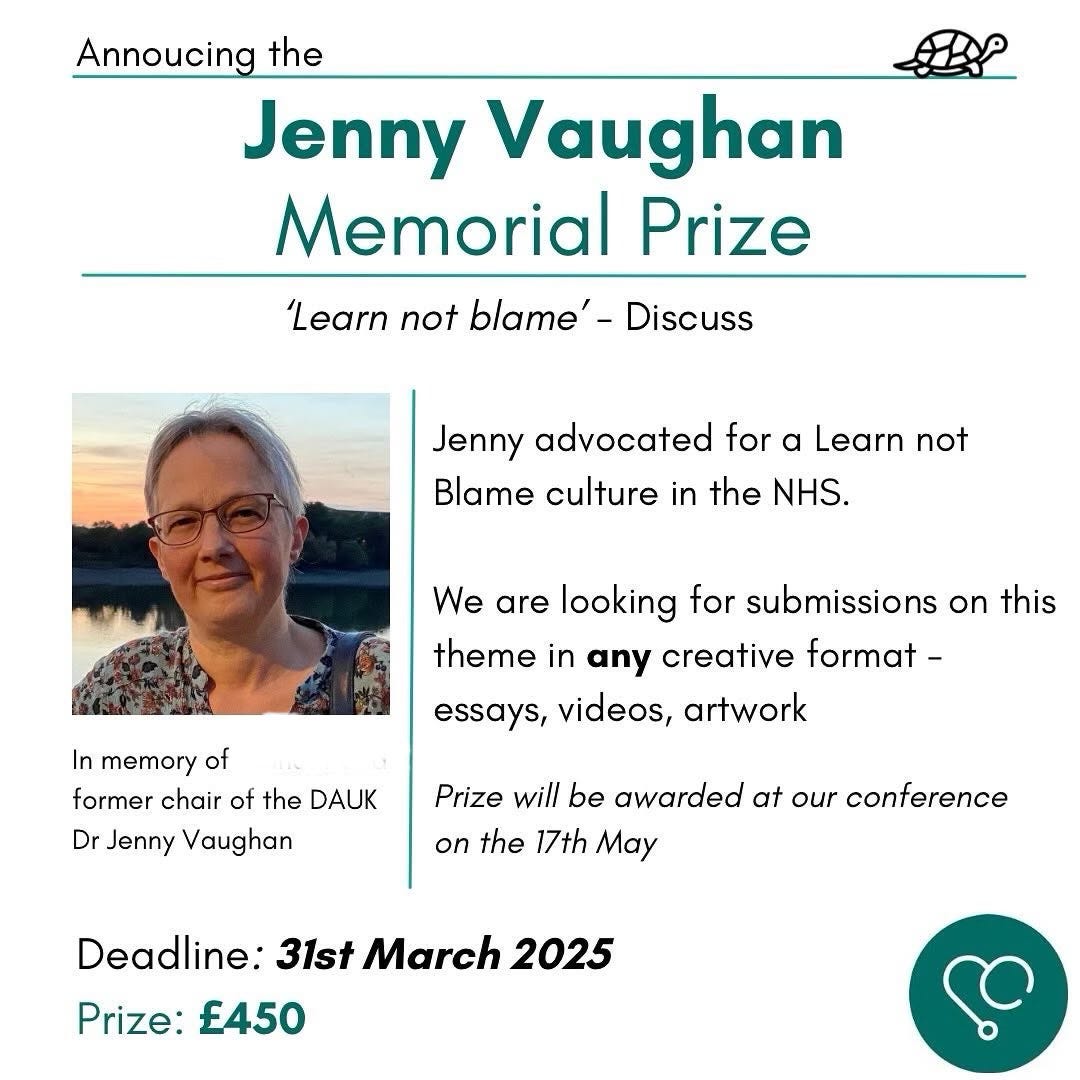

This long read essay was submitted by Dr Adesh Ajmani as an entry to our Jenny Vaughan Memorial Prize

Introduction

Dishonesty is not a ‘defined concept’ in law and ‘is characterised more by recognition than by definition’ [1]. As stated by Foskett J in Fish v GMC [2], ‘an allegation of dishonesty…is…not easily defended and…can be career-threatening or even career-ending’. If any allegation of dishonesty is made against doctors, this would result in a fitness to practice investigation of ‘misconduct’ under s.35C(2) of the Medical Act 1983. The purpose of investigation is to determine if the doctor’s fitness to practice is impaired. Should the Medical Practitioner Tribunal Service (MPTS) find ‘impairment’ in a doctor’s fitness to practice, s.35D of the Medical Act 1983 lays out the possible sanctions to be applied. The options are erasure, suspension for up to 12 months on the register, or conditions to be imposed on their practice for up to 3 years. Although not defined under the Act, a finding of impairment can be a sanction in itself and if no fitness to practice impairment is found a warning can be issued. The objectives of the sanctions under s.35 of the Medical Act 1983 are to ‘protect patients, maintain public confidence and declare and uphold standards of professional conduct’. Honesty and probity are a seeming requirement for doctors with the General Medical Council (GMC) stipulating it in their guidance for doctors. ‘The over-arching objective of the General Council in exercising their functions is the protection of the public’. This encompasses protecting their health, safety and confidence in the medical profession.

This report seeks to deliberate the extent to which doctors found to have proven dishonesty by the MPTS are able to avoid erasure. Dishonesty of medical professionals is a present hot topic. Recent cases of Manjula Arora and James Ip broadcasted in the media sparks debate on the extent to which the overarching function of ‘protecting the public’ is maintained. Consequently, it is crucial to address this current issue. Although critiques have addressed the comparison of dishonesty cases between doctors and lawyers, this is beyond the scope of this paper. The aim of the report will be achieved by firstly revisiting the legal test for dishonesty, before moving on to review when fitness to practice is not impaired. Then, the report will analyse whether a single act or persistent acts of dishonesty result in erasure, followed by finally evaluating the impact of insight, remorse and remediation. In each section, the implications for protecting patients and the public will be explored. In view of the arguments that will be outlined, ultimately, this report will conclude that doctors subject to a finding of dishonesty will often avoid erasure.

The test for dishonesty

Before reviewing medical dishonesty cases it is useful to review the legal test for dishonesty. The original two-part test to prove dishonesty from R v Ghosh states ‘i) was D’s conduct dishonest by the lay objective standards of ordinary reasonable and honest people? If the answer is no, then D was not dishonest, but if the answer is yes, ii) did D realise that ordinary honest people would so regard his behaviour?’ D will be found dishonest if both parts is ‘yes’’. However, since Ivey there has been removal of the second limb of this test. Additionally, there has been a shift to the civil burden of proof on the ‘balance of probabilities’.

No finding of ‘impairment’ in fitness to practice

The four stages of the MPTS hearing begins with i) the proof of facts, ii) head of impairment in which dishonesty would come under ‘misconduct’, iii) decision if fitness to practice is impaired, v) if fitness to practice is impaired then sanction follows. A doctor is able to avoid any sanction, including erasure, if their fitness to practice has not been found impaired, despite being guilty of dishonesty. The tribunal determined that Dr Uppal’s fitness to practice was not impaired because ‘this was an isolated episode’. It was further justified that because it ‘was not for financial gain and did not seem to benefit her personally in any way’ she did not pose a risk to patients or the public. In order to determine if a doctor’s fitness to practice is impaired, it involves looking forward at their behaviour and actions since the allegation, not retrospectively. Once the tribunal are ‘satisfied that the doctor’s fitness is not impaired’ it can issue a warning if deemed appropriate to do so. In this case ‘Dr Uppal had demonstrated insight and taken steps to avoid any repetition’ and thus a warning was given. This case is an example when doctors facing an allegation of dishonesty are able to avoid erasure as no impairment was found.

The tribunal’s approach from Uppal can be identified in a more recent case of General Medical Council v Armstrong. At the ‘impairment’ stage in the MPTS investigation, it found Dr Armstrong to be highly insightful, taking full responsibility for her actions. Therefore, it did not find her fitness to practice impaired. However, this was appealed by the GMC to the High Court and the court quashed the MPTS decision finding Dr Armstrong’s fitness to practice impaired. Arguably these cases, whereby a doctor is found not to be impaired despite committing a dishonest act, are problematic. Firstly, there is no statutory definition of impairment and it has been described as ‘elusive’. Further, the MTPS justification in these cases is because it was an isolated incident with repetition to be unlikely, no intent for personal benefit and is an exceptional case. Respectfully, this is oversimplistic and an oversight of the tribunal which fail ‘to engage with…factors tending to a finding of impairment’. This implies the MPTS may not maintain the overarching function to protect the public because it inappropriately determines no impairment in a doctor’s fitness to practice.

Persistent dishonesty or a single act

Notwithstanding the outcomes of the cases discussed in the previous section, a finding of dishonesty is ‘egregious’. It will be difficult to persuade the tribunal that doctors fitness to practice is not impaired. Thus, once impairment is found a sanction then follows. It has been cogently asserted by critiques, the MPTS Indicative Sanction Guidance and case law that persistent dishonesty is likely to lead to erasure from the register. Allegations of persistent dishonesty can either pertain to recurrent acts or the maintenance of innocence throughout the case, which ‘merited erasure’. Olatigbe v General Medical Council resulted in a judgment for erasure by the MPTS as his ‘serial dishonesty’ was ‘fundamentally incompatible with continued registration on the medical register’. This is resonated in the case of a former army doctor Derek Keilloh, who ‘maintained his dishonesty account over several years’ of the investigation. He initially faced one allegation of dishonesty during his deployment. Nevertheless, as he ‘stuck by his story’ this was deemed as ‘persistent dishonesty’ and resulted in erasure. Despite him being described as an ‘honesty, decent man of integrity’, the tribunal justified its decision to remove him from the register because ‘patients and the public must be confident that the doctor who treats them is competent and trustworthy.’ Erasure can be avoided if there is an admission of guilt from the outset which means the doctor is likely not be found impaired. Striking balance between rejected defence and doctors’ right to a fair trial increases the complexities in these dishonesty cases, however this is beyond the scope of this report.

At this point it is necessary to address that persistent dishonesty may not necessarily result in erasure. Sharief v GMC concerned a doctor’s repeated acts of dishonesty in conducting clinical trials yet was given a 12-month suspension by the tribunal. On appeal, the High Court judge found ‘it is unusual for cases involving findings of dishonesty by a disciplinary body in relation to a professional person not to result in erasure or striking off.’ The judge’s assertion of ‘unusual’ is inconsistent with other proven dishonesty cases, as will be discussed later. Cases of dishonesty resulted in a suspension more than erasure. There is ‘higher level of tolerance of dishonesty than was expected, with less than half of these cases resulting in erasure and a number of cases where only lower-level sanctions were employed.’ This suggests there is disparity between assertions made in judgments that ‘the Bolton principles apply equally to doctors’ and the extent to which in reality the Bolton Principles are being applied in medical dishonesty cases. This offers an explanation why many dishonesty cases have shown that doctors have been able to avoid erasure, with only approximately 40% erased.

Similarly, despite continued dishonesty Dr James Ip was able to avoid erasure. A consultant paediatric cardiac anaesthetist was found to be using his wife’s railcard for travel. Despite his ‘glowing testimonials from colleagues’, a clause in the sanction guidance means ‘evidence of clinical competence cannot mitigate serious and/or persistent dishonesty’. Initially his lawyer asked for Dr Ip’s fitness to practice being found not impaired and for a warning to be issued. But the tribunal asserted that 6-month suspension was ‘appropriate to reflect the seriousness’ of Dr Ip’s ‘repeated’ actions of dishonesty. Given James Ip’s acts were recurrent and he benefitted financially, this consequently was not considered to be low level dishonesty. It must be considered what distinguishes these cases of persistent dishonesty to those mentioned previously which led the tribunal to avoid a judgment for erasure. The case of Derek Keilloh in 2012, and Sharief in 2009 both had different sanctions, one resulting in erasure and the other in suspension. Likewise, the case of Olatigbe in 2019 resulted in erasure and Dr James Ip in 2023 resulted in suspension. It does not appear that the different sanctions had any correlation to when the test for dishonesty changed in 2017. Therefore, it is arguable the new test for dishonesty outlined in Ivey is not simple to apply and does not make proving dishonesty easier. This notion is also offered by Middleton who emphasises this test is ‘circular’. The ambiguous test lends itself to be openly interpreted and applied differently by the tribunal, which denotes the variation in its judgments for determining sanctions for persistent dishonesty.

Although there have been inconsistencies in the sanctions given for persistent dishonesty, if a single act of dishonesty has been committed, it appears erasure will be avoided and instead suspension is likely. Jasinarachchi v General Medical Council involved a singular incident on inappropriately completing a cremation form. The MPTS offered explanation as to why it did not deem erasure to be necessary, because ‘it was a single episode in an otherwise unblemished career’ and ‘his dishonesty was not premeditated’. The MTPS finding the doctor in Jasinarachchi impaired is disproportionate to their findings only two years prior in the case of Uppal. The MTPS justified it did not find Dr Uppal to be impaired because it was ‘isolated’ and the dishonest act was not done for her benefit. Notwithstanding similar reasoning declared in both cases, there is opposition in the sanctions it applied. This arguably casts doubt over the MPTS in its handling of such cases and its ability to protect the public and patients as its judgments are ‘unclear’.

Further evidence to support that a single act of dishonesty does not end in erasure is seen in the allegation against a locum GP, Manjula Arora. She was given a sanction of ‘suspension for dishonesty.’ This was concluded because she asserted that she had been ‘promised’ a laptop from her trust, when this exact word was not used. An uproar among doctors called for an independent review. This case raised several concerns over doctors fitness to practice investigation process. On the surface it appears this one-off act of alleged dishonesty meant erasure was avoided. However, on deeper scrutiny a pivotal concern was that ‘the case was ever brought to a fitness to practise hearing in the first place’ and should have been managed locally. The GMC issued guidance in March 2021 which outlines that low level dishonesty cases do not need to be referred to the tribunal for full investigation. It is disconcerting that Dr Arora did not see the benefit of this. The independent review even provided recommendations to the GMC to improve their ‘low level…dishonesty guidance’ to give ‘those making decisions enough flexibility; and/ or…supporting information…to ensure they fully understand the discretion they have in each case in order to make the right decision.’ Further, it has been suggested in this case the ‘legal test around dishonesty…was wrongly applied’, and ‘had that test been applied correctly, the allegation against Arora would never have made it to a tribunal’. This ‘means that the findings of dishonesty, impairment, and sanction should not stand’. The tribunal ‘failed to look at all the evidence…before imposing a sanction’ and ‘did not provide logical answer to the standards of ordinary decent people’. The GMC even apologised to Manjula Arora for their handling of the case after imposing a one-month suspension. This case demonstrates erasure can be avoided because inappropriate cases are brought to the tribunal in the first instance. Given its inappropriate handling of the investigation, the GMC and thus MPTS’s credibility is questioned along with its ability to meet the statutory overarching function of ‘protecting the public’.

Insight, Remorse and Remediation

When the doctor is disengaged in the process, an allegation of dishonesty can result in erasure and is not easy to remediate. This assertion is supported by Case ‘where erasure was ordered it tended only to be in cases where dishonesty was accompanied by…total disengagement from the regulatory body…' Despite initial allegations being withdrawn in Oluwashegun v GMC, because the doctor did not engage or comply with the interim orders, this led to their erasure. Through not engaging in the process, the doctor illustrates their lack of respect to the process and highlights their poor attitude which would not be in keeping with a remorseful, insightful doctor that the tribunal may want to keep on the register.

Accordingly, a demonstration of insight by the doctor influences the tribunal’s decision on whether fitness to practice is impaired and as well as the sanction given. If there is continual denial of their wrongdoings, the doctor will likely be found impaired as this exposes their ‘lack of insight into their misconduct’. The recent case of Sawati is significant when it comes to insight in dishonesty cases. The tribunal’s judgment called for erasure, but after appealing it was quashed and remitted to a different tribunal. It reiterated that good character should be used as consideration before ‘any conclusion of dishonesty’ is found and not after.

Remorse can be demonstrated in the doctor’s action. Dr Martinez whose remediation ‘totalled seven hours’ of ‘courses on ethics and professionalism’ ‘did not convince the tribunal’ and thus erasure followed. In contrast, Dr Armstrong was able to avoid erasure because she was fully committed to the process, even noted by the tribunal in its judgment that she left her family in Australia to attend the hearing. The MTPS believed this showed ‘genuine remorse’. In Bawa-Garba, the original MPTS decision that erasure was not necessary was because it was satisfied that she demonstrated remorse, remediated her actions, and reflected thoroughly which denotes her insight. However, unlike Dr Armstrong, Dr Bawa-Garba did not attend her hearing in person and therefore the tribunal were unable to conclude that she had full insight. This emphasises the extent to which showing insight is crucial to influence the tribunal’s decision for sanction. It is challenging to distinguish between insight, remorse, remediation as these ‘attitudinal’ factors overlap. There is no accepted definition for them. Nevertheless, it is notable that the tribunal must scrutinise the evidence to identify genuine remorse and expression of apology. This is because if an apology is shown after the allegations, ‘there is reason to doubt that any expressions of remorse and remediation are genuine’ and the tribunal should not give this much bearing in the decision making.

On the other hand, if there is less than convincing insight shown and ‘the Panel cannot be satisfied’, this has not necessarily resulted in erasure. The High Court judge in Pillai state these cases need to be balanced ‘one public interest against another’. In other words, although sanction is a seeming requirement to protect patients, the doctor is also of ‘great value’ to his patients. Therefore, perhaps the reason why many dishonesty cases have avoided erasure, is due to the invaluable skills and knowledge a doctor can offer when weighed up against their risk of harm to patients. Other wider socio-economic reasons may be considered by the tribunal when judging sanctions. Doctors facing fitness to practice investigations significantly impacts on their mental health. 25% committed suicide between 2005 and 2013. More recent data evidence that ‘78% said being under investigation had damaged their mental health’ and ‘the GMC has reported identifying 5 suicides among 29 doctors who died while under investigation in 2018, 2019 and 2020.’ Moreover, many doctors are leaving the NHS and perhaps sanctions of erasure are avoided in an attempt to preserve the current medical specialists in the UK. A recent survey undertaken by the Medical Protection Society (MPS) ‘found that 8% of the doctors had left medicine and 29% had considered doing so’ after facing fitness to practice investigation. Nevertheless, retaining doctors at the expense of compromising patient safety and public confidence is an important discussion but is beyond the scope of this report. The reasons discussed in this section supports the assertion that doctors found to have committed dishonesty are able to avoid erasure to an extent.

Conclusion

This report has provided a deeper insight into the extent to which doctors who have committed an act or acts of dishonesty are able to avoid erasure. The first instance in which erasure can be avoided, is if no impairment has been found in the doctor’s fitness to practice. Although, this is less likely as acting dishonestly means it is difficult to find no impairment. It can be seen that sanctions in cases of persistent acts of dishonesty are inconsistent, with some resulting in the sanction of erasure and some resulting in suspension. However, a single dishonest act is likely to avoid erasure. Exhibiting remorse, insight and remediation can veer in the doctor’s favour as these impact the tribunal’s decision for sanction. Doctors who fully engage in the process allows the MPTS to observe their good attitudinal qualities of insight. In light of the discussion presented in this report, there is a convincing argument that doctors found by the MPTS to have committed an act or acts of dishonesty are able to avoid erasure.

Bibliography

Cases

Atkinson v General Medical Council [2009] EWHC 3636 (Admin)

Bawa-Garba v GMC [2018] EWCA Civ 1879

Bolton v Law Society [1994] 1 WLR 512

Brookman v General Medical Council [2017] EWHC 2400 (Admin)

Cheatle v General Medical Council [2009] EWHC 645 (Admin)

Dr Fazal Hussain v GMC [2014] EWCA Civ 2246

Fish v GMC [2012] EWHC 1269 (Admin)

General Medical Council v Armstrong [2021] EWHC 1658 (Admin)

Ghosh v GMC [2001] 1 WLR 1915

Giele v General Medical Council [2005] EWHC 2143 (Admin)

GMC v Bramhall [2021] EWHC 2109

GMC v Chandra [2018] EWCA Civ 1898

Ivey v Genting Casinos [2017] SC 67

Jasinarachchi v General Medical Council [2014] EWHC 3570

Meadow v General Medical Council [2006] EWCA Civ 1390

Olatigbe v General Medical Council [2019] EWHC 3283 (Admin)

Oluwashegun v General Medical Council [2015] EWHC 2146 (Admin)

Pillai v General Medical Council [2009] EWHC 1048

Re H (Minors) (Sexual Abuse: Standard of Proof) [1996] AC 563

R on the application of Khan v GMC [2008] EWHC 3509

R v Ghosh [1982] EWCA Crim 2

Sawati v GMC [2022] EWHC 283

Sharief v GMC [2009] EWHC 3737

Sharma v GMC [2014] EWHC 1471

The General Medical Council v Dr Kennedy Krishnan [2017] EWHC 2892 (Admin)

The Professional Standards Authority v GMC & Igwilo [2016] EWHC 524

The Professional Standards Authority v GMC & Uppal [2015] EWHC 1304 (Admin)

Yeong v GMC [2009] EWHC 1923 (Admin)

Derek Kellioh, 2012

James Ip, Jan 2023

Manjula Arora, May 2022

Ramon Martos-Martinez, Aug 2019

Legislation

Medical Act 1983

Books

Oliver Quick, ‘Chapter 3 - Trust and Regulation’ in Regulating Patient Safety (Cambridge University Press, 2017)

Other:

Caitlin Tilley, ‘GP suspended for ‘dishonesty’ after saying she had been ‘promised’ laptop’ (Pulse today, 23 May 2022) <https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/news/regulation/gp-suspended-for-dishonesty-after-saying-she-had-been-promised-laptop/> last accessed 15/05/23

General Medical Council, Co-chairs of Dr Arora case review publish findings (2 Nov 2022) < https://www.gmc-uk.org/news/news-archive/co-chairs-of-dr-arora-case-review-publish-findings> last accessed 16/05/23

General Medical Council, Examples for decision makers of low level violence and dishonest (GMC 2021)

General Medical Council, Good Medical Practice (GMC 2013).

General Medical Council, Guidance for decision makers on allegations of low level violence and dishonesty (GMC 2021)

General Medical Council, Making decisions on cases at the end of the investigation stage: Guidance for the Investigation Committee and case examiners (GMC 2021)

General Medical Council, Supporting vulnerable doctors, Report on doctors who have died while under investigation or during a period of monitoring (GMC 2022)

Iqbal Singh, Martin Forde, ‘The GMC’s handling of the case of Dr Manjula Arora, An independent learning review’ (2022)

Jess Warren, ‘Great Ormond Street doctor suspended for 'serious' dishonesty’ (BBC, 23 May 2023) < https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-65052322> last accessed 15/05/23

MPTS, Indicative Sanction Guidance (MTPS 2020)

Articles

Cathal T. Gallagher, David H. Reissner, ‘The Concept of Dishonesty in British Medical Discipline’ (2022) 108 Journal of Medical Regulation 20-24.

Clare Dyer, ‘Cardiologist is struck off for repeated dishonesty’ (BMJ 2021) < https://www.bmj.com/content/373/bmj.n1646> last accessed 10/05/2023

Clare Dyer, ‘Consultant is suspended for six months for travelling on tube without ticket’ (BMJ 2023) <https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/380/bmj.p707.full.pdf> last accessed 15/05/23

Clare Dyer, ‘Doctor faces new charges of wrongfully practising as a GP after GMC wins appeal’ (BMJ 2022) <https://www.bmj.com/content/379/bmj.o2552> last accessed 10/05/23

Clare Dyer, ‘Doctor previously struck off for lying and plagiarism is restored to medical register’ (2021) 372 BMJ (Online) 34.

Clare Dyer, ‘Doctor who denied he saw Iraqi detainee’s injuries is struck off medical register’ (BMJ 2012) <doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8686> last accessed 10/05/2023

Clare Dyer, ‘MC reduces investigations of minor cases that pose no risk to public safety’ (BMJ 2021) <https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n780> last accessed 10/05/23

Clare Dyer, ‘New test in tribunal cases could find more doctors acted dishonestly’ (BMJ 2017) <doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5453> last accessed 10/05/2023

Clare Dyer, ‘Tribunal told to think again after allowing doctor who wrote prescriptions without seeing patients to continue practising’ (BMJ 2023) <https://www.bmj.com/content/381/bmj.p1006> last accessed 15/05/23

David Middleton, ‘First Do No Harm, or Eat What You Kill?: Why Dishonesty Matters Most for Lawyers’ (2014) 17 Legal Ethics 382

Denis Campbell, ‘Almost one in three doctors investigated by GMC ‘have suicidal thoughts’ (The Guardian 27 April 2023) <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/apr/27/almost-one-in-three-doctors-investigated-by-gmc-have-suicidal-thoughts> last accessed 10/05/2023

Ed Madden, ‘Salaried GP engaged in ‘serial dishonesty’’, (2020) Irish Medical Times <https://www.imt.ie/opinion/ed-madden/salaried-gp-engaged-serial-dishonesty-14-01-2020/> last accessed 10/05/2023

Elisabeth Mahase, ‘Manjula Arora: GMC won’t challenge appeal and calls for sanctions to be dropped by court’ (BMJ 2022) <https://www.bmj.com/content/377/bmj.o1583> last accessed 10/05/23

Elisabeth Mahase, ’Doctors express “grave concerns” at GMC action after GP is suspended over laptop claim’ (BMJ 2022) <doi:10.1136/bmj.o1324> last accessed 16/05/23

Helen Grote, Flora Greig, ‘Junior doctors and fitness to practice procedures in the UK: analysis of factors prompting tribunal referrals and outcomes’ (2021) 97 Postgrad Med J 623–628.

Iqbal Singh, chair, Martin Forde, ‘What can we learn from the Manjula Arora case?’ (BMJ 2022) < https://www.bmj.com/content/379/bmj.o2634> last accessed 10/05/2023

Javier Caballero and Steve Brown, ‘Engagement, not personal characteristics, was associated with the seriousness of regulatory adjudication decisions about physicians: a cross-sectional study’ (2019) 17 BMC Medicine 1-10.

Jay Ilangaratne, ‘Manjula Arora: would most “ordinary decent people” conclude that she had acted dishonestly?’ (BMJ 2022) <https://www.bmj.com/content/378/bmj.o1651> last accessed 10/05/23

John Martyn Chamberlain, ‘Malpractice, Criminality and Medical Regulation: Reforming the Role of Fitness to Practise Panels’ (2017) 25 Med L Rev 1.

Melody Carter, ‘Deceit and dishonesty as practice: the comfort of lying.’ (2016) 17 Nursing Philosophy 202

Paula Case, ‘Doctoring confidence and soliciting trust: models of professional discipline in law and medicine’ (2013) 29 Professional Negligence 87-107.

Paula Case, ‘Putting Public Confidence First: Doctors, Precautionary Suspension and the General Medical Council.’ (2011) 19 Med L Rev 339.

Paula Case, 'The Good, the Bad and the Dishonest Doctor: The General Medical Council and the Redemption Model of Fitness to Practise' (2011) 31 Legal Studies 591

R. Searle et al, ‘Bad apples, bad barrels or bad cellars? Antecedents and processes of professional misconduct in UK Health and Social Care: insights into sexual misconduct and dishonesty’